Indiscriminate selling has created buying opportunities in high yield

If there were ever a case of throwing the baby out with the bathwater, high-yield investors today are engaged in it.

There are certainly legitimate concerns surrounding the energy and, to a lesser degree, the metals and mining sectors of the market, but we see little reason to expect the kind of widespread deterioration in fundamentals that the market is currently pricing in.

As of this writing, the high-yield market, as measured by the Bank of America Merrill Lynch (BofA ML) U.S. High Yield Master II Index, offered a yield to worst of about 9.5%, with a spread over U.S. Treasuries of approximately 800 basis points.1 Those levels imply a default rate for the market of around 8.5%,2 which would be more than four times today's rate and a level we haven't seen since coming out of the financial crisis.

The energy sector today represents only 10% of the total high-yield market, and while we believe an increase in defaults among energy companies is probably inevitable, the magnitude of collapse that would be required to drive the overall high-yield market default rate near implied default levels is extremely unlikely. However, the consequence of the indiscriminate selling that's been happening across the asset class has been sharp declines in bond prices, which has led to roughly 30% of the market trading at extreme yields—in excess of an 11% yield to worst.2

Outlook for oil calls for continued—but tapering—oversupply

With capital markets often whipsawed by investor sentiment, there's something reassuring about the cause of the precipitous drop in oil prices: Recent declines have been driven by that most fundamental of economic factors, supply and demand. Global demand, led by the slowdown in China and Europe, has been declining over the past year plus, and there may be more softening ahead. But the real issue has been on the supply side; versus a year ago, oil inventories today are up about 9% in aggregate, which is emblematic of the global glut of supply. Iran, for its part, with economic sanctions recently lifted, is expected to increase exports in the coming months, potentially by as much as 500,000 barrels a day, and the timing is far from ideal.3 Many emerging-market exporters depend on oil revenues to finance government operations, and they're inclined to continue to operate at maximum output regardless of price.

That said, there are reasons to believe the level of oversupply will begin to taper. Most developed-market commercial producers have announced plans to reduce spending on exploration and production and to trim activity across the board at production facilities. In the United States, the rig count, a bellwether for future supply levels, fell to 47 last week in the Bakken region of North Dakota, its lowest level since August 2009; one year ago, North Dakota had 157 actively producing rigs.4

Any good news could be a catalyst for gains

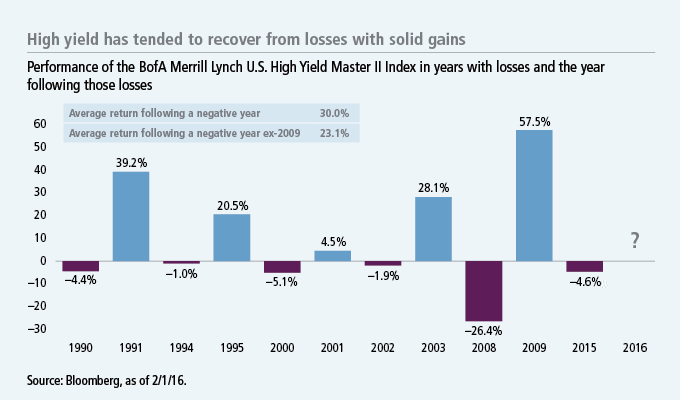

While it's impossible to predict how long oil will trade at its current levels of around $30 a barrel, many believe today's prices appear oversold. Our analysis suggests prices in the neighborhood of $40 to $50 a barrel would be more sustainable over longer time periods, and even a moderate uptick in oil prices from today's lows could be a catalyst for squeamish high-yield investors to reenter the market. Since 1987, which was the first full calendar year for the BofA ML U.S. High Yield Master II Index, the high-yield market has only had six calendar years of negative returns and has never experienced two consecutive years of negative performance; in fact, the high-yield market has historically exhibited strong returns following a negative calendar year return, with an average increase of 30%, 23% excluding 2009. While history doesn't always repeat itself, markets tend to move irrationally both on the way up and on the way down. Given current valuations in the market and our expectations for low default rates outside of commodity-related sectors, we expect high yield is poised to pleasantly surprise investors in 2016, with the possibility of additional upside if spreads compress.

1 Manulife Investment Management, Merrill Lynch, as of February 2016. 2 "U.S. High Yield and Leveraged Loan Strategy," J.P. Morgan, January 2016. 3 "Saudi Arabia, Shale & Iran: Everything You Need to Know about the Oil Crisis," forbes.com, January 2016. 4 "Despite holding steady, North Dakota braces for oil supply crash," blogs.platts.com, January 2016.

The Bank of America Merrill Lynch (BofA ML) U.S. High Yield Master II Index tracks the performance of globally issued, U.S. dollar-denominated high-yield bonds. It is not possible to invest directly in an index. Past performance does not guarantee future results.